Blog

New report sheds light on payment flows in the pharmaceutical supply chain, including the role of 340B and vertical integration

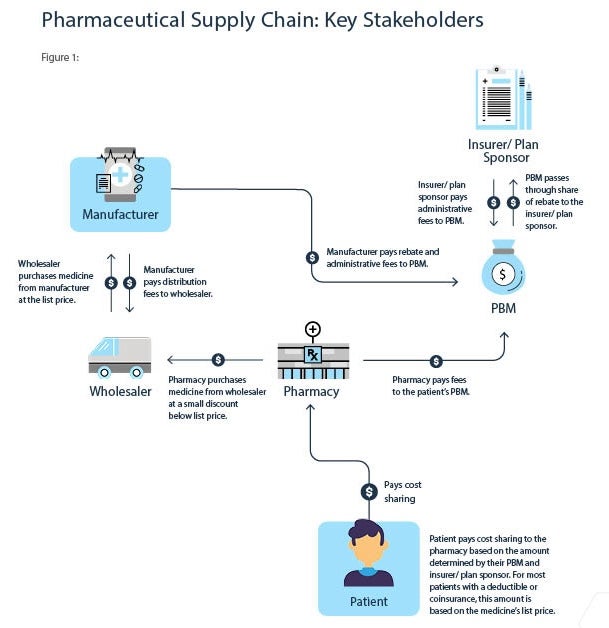

A new report explains the flow of dollars through the pharmaceutical supply chain for commercially insured patients taking retail medicines and details how transactions between stakeholders affect patient costs at the pharmacy counter. The report also highlights how the 340B hospital markup program and increased consolidation and vertical integration among supply chain entities raises the cost of medicines for patients and employers.

The path a medicine takes from the biopharmaceutical manufacturer to the patient involves a complex supply chain, including wholesalers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), insurers, and pharmacies.

The report provides three hypothetical examples to illustrate how payments flow through the supply chain when a patient is purchasing a medicine in their deductible, with a copay or at a 340B contract pharmacy.

Middlemen pocket savings meant for patients.

Manufacturers provide billions in rebates and discounts to PBMs and insurers, which can lower a medicine’s average net price by 50% or more. However, PBMs and insurers rarely pass these savings to patients at the pharmacy counter, often leaving patients to pay more than their insurer or PBM. Rebates and discounts are often tied to the list price of medicines, which experts have noted may incentivize PBMs and insurers to favor drugs with higher list prices over lower cost alternatives. At the same time, insurers shift costs onto patients through high deductibles and coinsurance, which are also often based on the list prices.

Here is an example of what happens when a patient fills a prescription and has not yet met their deductible:

- Jane takes a blood pressure medicine with a $100 list price. Because Jane hasn’t met her deductible, her insurer does not cover any costs for this prescription. Her PBM, however, still receives a rebate from the manufacturer, and shares a portion with the insurer. The PBM and insurer earn $10.65 and $23.10, respectively, from rebates and fees, while Jane pays $101.10 – a higher price than any stakeholder in the supply chain.

Here is an example of what happens when a patient fills a prescription and has met their deductible but has a required copayment:

- Erik takes a blood pressure medicine with a $100 list price and has met his deductible. He pays a $40 copayment. The insurer/ plan sponsor spends $38 after accounting for the rebates and fees they receive. Ultimately, Erik pays more for his medicine than his insurer and PBM.

Big, tax-exempt hospitals and clinics abuse the 340B program by marking up medicines.

The 340B hospital markup program allows big, tax-exempt hospitals and clinics to purchase medicines at a low cost, sometimes as low as a penny, and then significantly mark up the price. When the medicines are dispensed at a contract pharmacy, patients, insurers, and employers pay the full marked-up price which is a hidden tax on medicines.

Here is an example of what happens when a patient fills a 340B eligible prescription at a 340B contract pharmacy:

- Scott takes a blood pressure medicine with a $100 list price and fills it at a 340B contract pharmacy. The 340B hospital buys the medicine for $28, dispenses it through its contract pharmacy and receives $100.85 in return. The patient pays $40 in cost sharing and gets no benefit from the 340B discounted price. That means the hospital paid less than the patient while profiting $57.60 and earning twice as much as the manufacturer.

Vertical integration and consolidation put profits before patients.

The increase of vertical integration and consolidation among insurers, PBMs, pharmacies and providers has enabled these organizations to profit from nearly every transaction in the pharmaceutical supply chain through fees, spread pricing, and opaque practices. In fact, half of every dollar spent on medicines goes to middlemen and others that do not make the medicine, highlighting a growing problem that spending on medicines is increasingly being used to subsidize many parts of the health care system, often at the expense of patients.

Middlemen control what patients pay at the pharmacy counter, as well as which medicines patients can get and where they can get them. Vertical integration also financially incentivizes PBMs to steer patients towards the pharmacies they own.

To treat the problem, we must diagnose it correctly first. For policymakers to address rising health care costs, they must address where half of prescription drug spending is going – to entities that do not make medicines.

Rachel Weissman

Rachel Weissman