Pediatricians need help. They’re battle against historically high rates of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) as well as influenza and COVID-19 among their young patients—what some dub the tripledemic—puts a huge strain on the pediatric healthcare system.

This comes as no surprise to Daniel Rauch, M.D., the chairperson of the committee on hospital medicine for the American Academy of Pediatrics.

He told Fierce Healthcare that society has “not valued pediatric care. We’ve not responded to this the same way that we did with COVID and adult care [in March 2020] and that’s just a damning indictment of our national priorities in our healthcare system.”

That’s one of the points made this Tuesday in an opinion piece in STAT in which the authors likened what’s going on at pediatric hospitals and hospital wards because of the tripledemic to what happened at acute care hospitals swamped with COVID-19 patients in March 2020.

Sallie Permar, M.D., and Robert Vinci, M.D., wrote in STAT: “In March 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic swept across the United States, the nation’s pediatric providers and pediatric units immediately pitched in to treat adults sickened by this then-mysterious and deadly disease. But now that the pediatric community is facing its own March 2020 with the confluence of COVID-19, influenza, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), the response from outside this community has been slow.”

Permer is pediatrician-in-chief at NewYork-Presbyterian Komansky Children’s Hospital and chairperson of the Department of Pediatrics at Weill Cornell Medicine. Vinci is the chief of pediatrics at Boston Medical Center, and chairperson of the Department of Pediatrics at Boston University School of Medicine.

They added: “That says volumes about how the U.S. prioritizes—or more accurately doesn’t prioritize—the health of children.”

When asked if he agrees that the situation in pediatrics now is as bad as the situation had been in acute care hospitals in March 2020, Rauch responded, “Yes and no.”

He continued: “I’ll start with the ‘no’. We’re not seeing the increase in volume that we saw with adults. We’re just not. Adult volume went up hundreds of percent. And pediatric volume hasn’t gone up like that. For ‘yes’, the capacity to absorb that additional volume was there for adults, and it’s not there for pediatrics. The pediatric system is already pretty stretched and limited, and it doesn’t have the ability to expand like the adult systems did.”

Most children get RSV by the time they’re two years old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This year, pediatric beds are being filled with children ages three, four and five who have RSV.

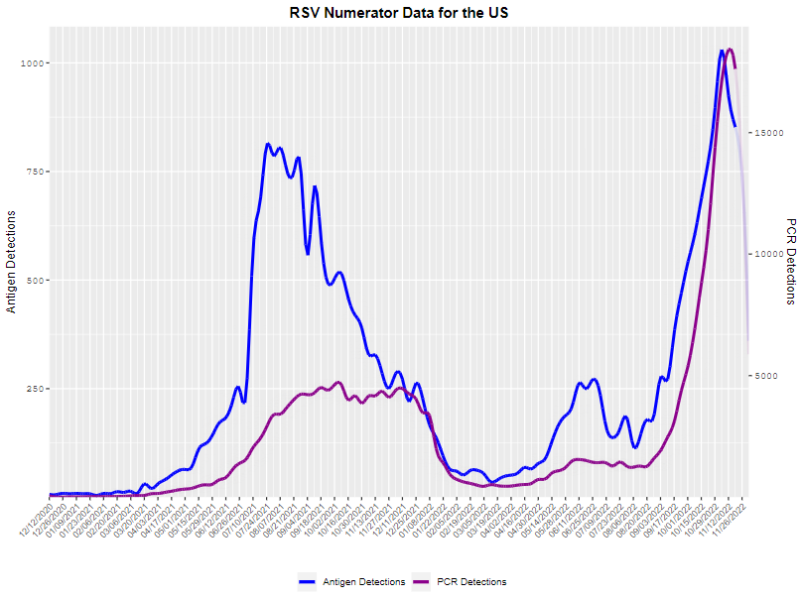

Some epidemiologists note that the mitigation efforts used to stave off COVID-19—masking, social distancing, hand washing—stopped influenza and RSV in their tracks, driving infection rates to historic lows in the 2020-2021 season. Now, both are coming back with a vengeance and children who usually acquire some immunity (though RSV can infect more than one time) by age two find themselves immunologically naive. For now, though, that’s just one theory.

“I can’t explain why we’re seeing really, really sick four-year-olds and five-year-olds when that just hasn’t been the pattern for RSV before,” said Rauch. “And I’ve actually learned through all of this. RSV kills almost as many adults and geriatric patients as the flu does on an annual basis. So, the reservoir is there in the community. And we’ve seen it for years, and it’s just acting different. I don’t know if it’s because those kids weren’t primed by prior infections. So, they’re getting it for the first time as opposed to the second or third time now.”

The RSV surge might have peaked in some parts of the U.S., such as the Northeast, he said. That means, he added, that the RSV numbers aren’t as “astronomically” high as they had been just a short time ago. But RSV usually continues to infect over the winter months.

“It’s just not going to be at that same incredibly high peak,” said Rauch. “You can get it in November and then again in March. Unfortunately, what we are seeing is a lot of flu, and the flu numbers are starting to skyrocket.”

Rauch also doesn’t fault physicians and other providers for not coming to the rescue of pediatric hospitals.

“It’s not like our colleagues who treat adults are sitting around doing nothing,” he said. “They are busy, and the flu is hitting adults as well as it’s hitting kids. So, there’s not that group of people who aren’t otherwise occupied.”

Rauch added that it’s more difficult for physicians to go from mainly treating adults to treating children than it is to make the transition the opposite way. Not only are the medications different but the way dose levels are calculated is different.

In their opinion piece in STAT, Permar and Vinci wrote about the “long-standing disparity in pay for pediatricians compared to those of physicians who treat adults, further contributing to the shortages in the pediatric workforce. Healthcare is funded in a way that indicates that the health of children is less important than the health of adults, a short-sighted and expensive choice.”

Rauch couldn’t agree more. “Unfortunately, pediatrics, I think, is the second lowest-paid, specialty. And if you look at what the average indebtedness of someone graduating from medical school in the United States—because it’s mostly privately financed—it’s really high. They could do other specialties and provide other needed services and not still be paying back their medical school loans when their own kids go off to college.”